|

"Easter" is a non-biblical word which does not appear anywhere in the Bible, but which began as an entirely unrelated pagan ritual. There is also no such thing as "Good Friday" in the Bible. Both terms represent false

.

"Easter" is viewed by many as a day to celebrate the resurrection of Jesus Christ.

However, in celebrating "Easter," millions focus mostly on that biogenetic

oddity known as the Easter Bunny without considering, "What does an

egg-laying rabbit have to do with Jesus Christ?"

While the Easter Bunny may be a cute tradition, it is totally incompatible with

the resurrection of Jesus Christ.

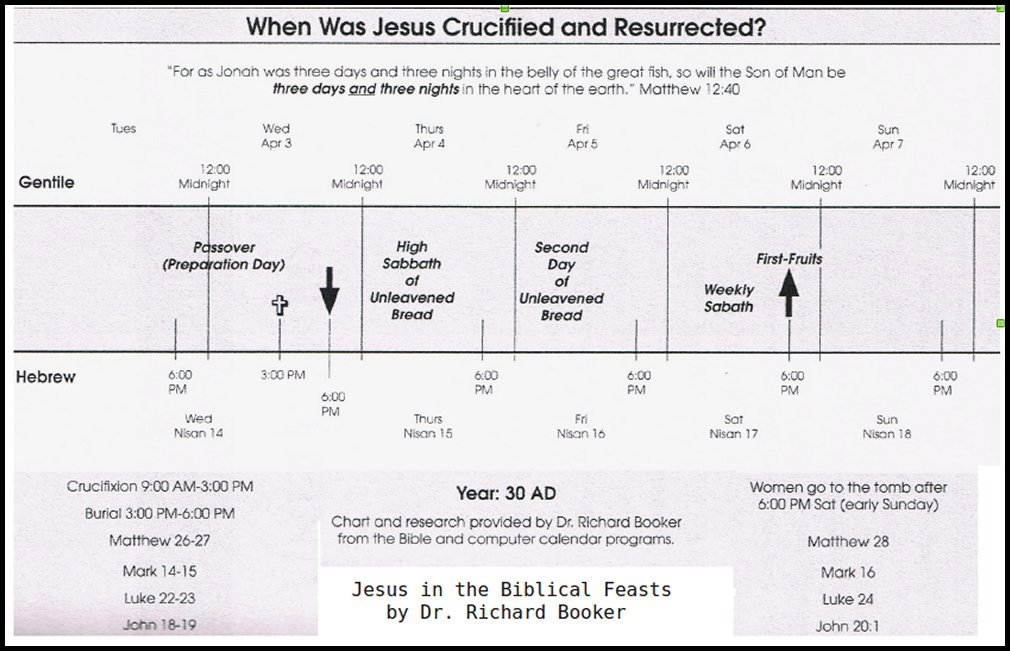

The word "Easter" is not found in any accurately translated text of the Bible. Articles about Easter in the Encyclopedia Britannica state: "There is no indication of the observance of a so-called Easter festival in the New Testament or in the writings of the apostolic fathers." Correct translations use the word Passover and definitely not Easter. The early Christian church, established in 31 A.D., observed the Passover, not "Easter." The Encyclopedia Britannica states: The sanctity of special times was an idea absent from the minds of the first Christians who continued to observe the Jewish festivals (see Leviticus 23 for an explanation of those festivals), although in a new spirit. The early church and Apostles never observed "Easter." The apostle John set the record strait in John 19:14 and 31 as to the day of Christ's death by telling us that Christ died and was buried at the end of the preparation day preceding the Feast of unleavened Bread. The preparation day fell on a Wednesday that year. (Note: The reference to the Passover in verse 14 noted above is to the oncoming festival of Unleavened Bread which the Jews incorporated into the Passover period.) Christ's body was taken down on Wednesday afternoon and placed in a tomb before Thursday the high day began. Therefore, Christ's body was in the tomb for three full 24-hour periods ... three full days and nights: Wednesday night, Thursday, Friday, and Saturday until the end or close of the Sabbath. Then, just before sunset (the time when days end and began in Bible times) on the regular weekly Sabbath (Saturday), Christ came out of his grave, His mission accomplished, having spent three full days and three full nights in the heart of the earth as He specifically stipulated that He would do in Matthew 12:40, and just as He had foretold in Mark 9:31 and John 2:19-21. The Easter myth of a Sunday morning resurrection collapses in light of these facts. The Scripture states that when Mary arrived at the tomb, Christ was already gone. Note: The fabrication of a "Good Friday" death and burial is also a myth that has no basis in fact. From Friday night to Sunday morning is only one and one-half days, not three days and three nights. Easter has nothing whatsoever to do with Christ. The historical record reveals the truth of its origins. That strange, non-biblical name, Easter, does have a religious meaning; but it is not Christian. Rather, the word Easter is derived from an ancient Teutonicgoddess of fertility named Estere, whose feasts were celebrated in the spring by her pagan adherents. Typically, the Estere celebration occurred in April, at which time she demanded sacrifices from her followers. Going back even further into antiquity, Easter can also be traced to the ancient goddess Ishtar, and is associated with the deification of women goddesses in various religion, up to and including the Catholic deification of Mary. The pagan roots of Easter do not end with just the name, however. The symbols of rabbits and eggs can also be traced to pagan fertility celebrations. The use of the egg goes back to ancient Mesopotamia where it was closely identified with another goddess of fertility, Astarte. The following quote from the ancient Egyptian historian Hyginus explains the connection: An egg of wondrous size is said to have fallen from heaven into the river Euphrates. The fishes rolled it to the bank, where the doves having settled upon it, hatched it, and out came Venus, who afterwards was called the Syrian Goddess [that is, Astarte]. (Visit www.historytelevision.ca/archives/easter/customs for more about the Easter egg tradition.) Some historians also claim that eggs were prominent in Egyptian temples and Druid springtime ceremonies. The Easter Bunny can also be traced back to the Teutonic pagan celebration of Estere or Astarte. It is in connection with this festival that the pagan adherents looked to the hare as a symbol of fertility because of its prolific nature. During this celebration, eggs were believed to have come from the hare as a symbol of a new, abundant spring. If you're wondering what Teutonic fertility goddesses have to do with Christianity, you're not alone. Biblically, there are no connections. Therefore the question remains: Why does Christianity celebrate Easter? To understand this part of the history of Easter, one has to examine the early development of modern Christianity. The Early Church. The early Church, to a large extent, was made up of Jewish converts. The first disciples of Christ were, of course, Jews; and the early adherents often first heard the Gospel message in the synagogues (Acts 9:20-21). The story of how the Gospel came to the gentile world is well rehearsed, and figures prominently in the story of Acts. When the doors of the Church were first opened to gentile converts, the early Church saw Christianity as being in harmony with the Old Testament. As such, the Old Testament holy days and the specific times at which they were observed were viewed as important and relevant to the new" faith of Christianity. It was not strange, therefore, that the early Church continued with the observance of Passover. It was not until later that the tradition of Easter developed among the gentile converts. Owing to a violent Jewish uprising crushed by Emperor Hadrian in 135 A.D., the Roman Empire began to enact laws especially hostile to the Jewish faith. As part of his retaliation against the Jewish rebels, Jerusalem was almost destroyed, and also renamed. Hadrian's edicts following the destruction of Jerusalem banned the practice of Judaism, including the observance of its holy days, and prohibited Jews from setting foot in Jerusalem. As a result of this attempted destruction of the Jewish nation, the hierarchy of the early Church was decimated. The leaders of the Church in Jerusalem, up until that time, had been Jewish: fifteen men recorded in all, spiritually descended from the original twelve apostles. Banning the Jews from Jerusalem, and from Roman society in general, led to a change in the entire nature of the church ... the congregations were now led by Gentiles, and were composed of Gentile converts. We are not Jews The Gentile, unlike the Jew, came from a religious culture steeped in mysticism, and was ignorant of the Old Testament scriptures. One historian summed up the difference between the ancient Jew and Gentile as this: Gentile Christians usually came from a background devoid of Scriptural knowledge. They did not have a natural appreciation for, allegiance to, or comprehension of the Scriptures, especially the Law and Prophets which they misunderstood. Origen, a famous Church leader of the third century, would go so far as to say that Greek philosophy was just as important to the Gentile as the Law was to the Jew in their understanding of the Gospel message. A contemporary of Origen's observed the following regarding those who advocated this approach: "They forsake the holy Scriptures of God, and study geometry, as may be expected of men who are of the earth, and speak of the earth, and are ignorant of Him that cometh from above. Some of them industriously cultivate the Geometry of Euclid; Aristotle, and Theophrastus, and are looked up to with admiration ..." The Christian Church's theological roots in the Old Testament were being severed during this period ... the Jewish leadership, influence, and theological perspective were slowly eliminated. Clearly, by the beginning of the second century, various Christian sects had begun to fuse Christian practices with pagan observances. New church leaders had taken the place of the old and taught Christianity in the tradition of Greek philosophy. It was during this time (135 A.D.) that the observance of Easter Sunday began and was set on a Sunday coinciding with a day of religious significance in the pagan world. Sunday was observed in Roman religious society as the day of the venerabili die Solis, or venerable Sun. This gave the evolving pseudo-Christian religion greater appeal to potential pagan converts. It was the natural progression of a church whose roots were becoming more firmly planted in pagan, Hellenistic traditions, as opposed to Old Testament tenets. Subtle desire to distance Christianity from Judaism gave way to overt anti-Semitism upon the official establishment of Easter as a well-known Christian holiday. Constantine The Great, the first Roman Emperor to embrace Christianity, officially recognized the observance of Easter as a national religious and civil holiday in 325 A.D. Constantine's decision to establish Easter was motivated, not only by a desire to separate Christianity from the moorings of Jewish influence, but also out of his unapologetic hatred for the Jewish people. As one historian noted, "It was probably the Emperor's passionate hatred of the Jews that decided the issue." Quoting from a later letter issued by the Emperor, the point is emphasized in his own words: "It appeared an unworthy thing that in the celebration of this most holy feast we should follow the practice of the Jews, who have impiously defiled their hands with enormous sin, and are, therefore, deservedly afflicted with blindness of soul. Let us then have nothing in common with the detestable Jewish crowd." The Quatrodecimen Some early church members--the Quatrodecimen, so named for their adherence to the 14th of Nisan (Jewish calendar) as the correct day for Passover observance--resisted the adoption of the pagan Easter as a Christian day of worship. An early Christian Bishop, Polycarp, engaged in a famous debate with the then Bishop of Rome in defense of the apostolic and biblical tradition of keeping Passover. After Polycarp, another minister in Asia (Asia Minor) named Polycrates came to the defense of the Passover, and penned an eloquent defense of its observance, citing the history of believers back to the Apostles before him who had kept it: All of these kept the fourteenth day of the month as the beginning of the Pascal festival, in accordance with the Gospel, not deviating in the least by following the rule of the Faith. Last of all I too Polycrates, the least of you all, act according to the tradition of my family, some members of which I have actually followed; for seven of them were bishops and I am the eighth, and my family have always kept the day when the people put away the leaven. So I, my friends, after spending sixty-five years in the Lord's service and conversing with Christians from all part of the world, and going carefully through all Holy Scripture, am not scared of threats. Better people than I have said: "We must obey God rather than men." After Polycrates, however, the proponents of Easter swallowed up most of what remained of the few adherents to the biblical tradition. Those who refused to convert were branded as heretics and had to flee persecution. They--the Quatrodecimen--were the remaining organized shreds of what had been the church established in Jerusalem in 31 A.D. The church that sprang forth under the protection of the Roman civil system observed different days and a different theology. Does it matter? The history of Easter is mired in ancient pagan custom, political compromise, and, in some respects, racism. But that's just it ... It's all history. Irrespective of what happened then ... today, the celebration is centered on Christ, right? And that makes celebrating Easter okay, doesn't it? Well, not according to the Apostle Paul, who when addressing the Corinthian church emphasized the importance of following the correct observance of the Passover: I praise you brethren, that you remember me in all things and keep the traditions as I delivered them to you" (I Corinthians 11:2). Speaking again of the tendency of some to waiver from the teachings of the Church, Paul issued a warning against such behavior: But we command you brethren, in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, that you withdraw from every brother who walks disorderly and not according to the tradition that he received from us. (II Thessalonians 3:6). Clearly, Paul admonished the church to remain faithful to the teachings delivered to them, including the observance of the Passover. The Apostles had taught the true doctrines of Christ, and taught the deep meaning of those observances to their congregations. It is clear that the Church's drift from the observance of Passover to the celebration of Easter was in contravention of the Apostles' instructions; and a breach of the long tradition rooted in the book of Exodus. In Matthew 7:21-23, Christ draws a line between those who follow Him and those who only profess a belief in Him: "Not everyone who sayas to me, Lord, Lord, shall enter into the kingdom of heaven; but those who do the will of my Father who is in heaven. Many will say to me in that day, Lord, Lord, have we not prophesied in your name? And in your name cast out devils? And in your name done many wonderful works? And then will I profess to them, I never knew you: depart from me, you who work iniquity." When much of the Christian world celebrates "Easter" on a day that was consecrated by men through political intrigue, religious compromise, and racism, one must ask: "Is this the correct way to memorialize the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ?" Remember, Jesus said: " ... In vain they do worship me, teaching for doctrines the commandments of men." (Matthew 15:9).

To celebrate "Easter" instead of the biblical Passover, is a tragic error

... one that all true believers should seriously reconsider.

|